China’s purchases of chipmaking equipment to decline in 2025, consultancy BERTRAMS | Reuters

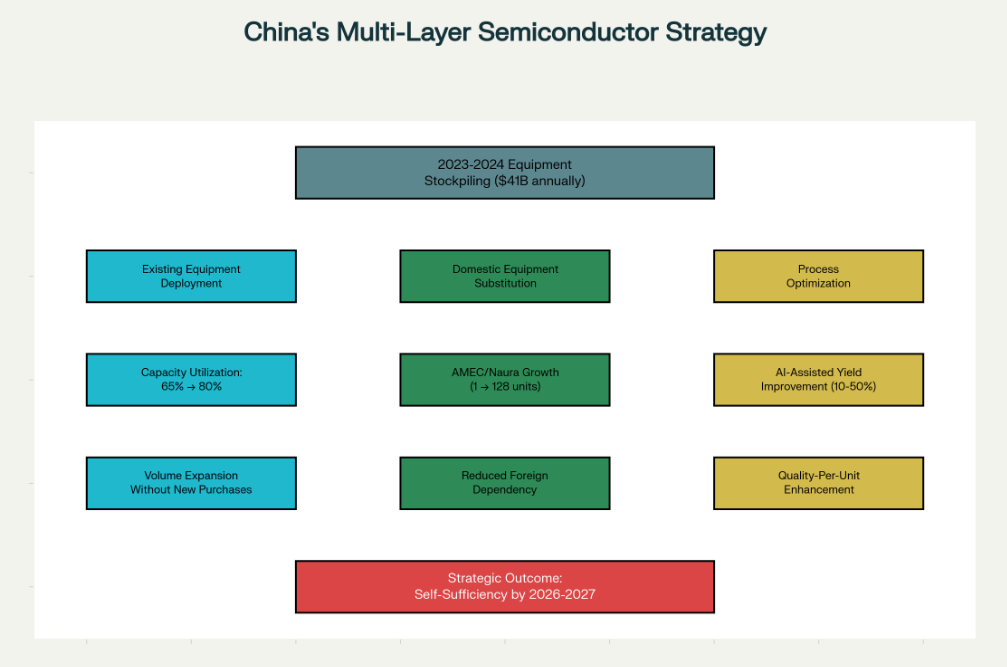

Our advanced Thesis: “The Illusion of Chinese Semiconductor Overcapacity – Hidden Capacity Expansion and Technological Acceleration Behind a Narrative of Decline”

Another Opinion is our critical view on a strategic misconception:

The prevailing pattern: China does not face any industrial critical shortage, neither crippled by overcapacity or enforcement into equipment retrenchment! – This assumption would barely see a much more complex reality:

- China is simultaneously executing a sophisticated capacity redirection and technological acceleration

- AI will fundamentally reshape their global semiconductor landscape by 2026-2027

- We argue, that the apparent decline in chipmaking equipment purchases represents not industrial failure, but strategic repositioning toward domestic production autonomy, hidden capacity expansion, and quality-per-unit improvements that are occurring “behind the scenes” at unprecedented velocity.

We anchor our thesis in the facts, that a decline in chipmaking equipment purchase is absolutely not an industrial failure, but only a strategic repositioning of China/Russia towards a domestic production autonomy with another hidden capacity expansion, and quality-per-unit improvement that will suddenly occur “behind the scene”.

The Deceptive Surface: Equipment Purchase Decline as Strategic Narrative

The observable metric that Western analysts focus on is superficially compelling:

- China’s purchases of chipmaking equipment declined from $41 billion in 2024 to an expected $38 billion in 2025, a 6% year-on-year drop, with global market share falling from 40% to 20%. This figure is accurate but profoundly misleading!

The narrative of “overcapacity” rests on three assumptions:

- that fabs built in 2023-2024 operate with excess idle capacity

- that reduced equipment spending signals technological stagnation

- that decreased foreign equipment imports indicate weakness rather than strategic substitution

The stockpiling dynamic that drove the 2023-2024 surge was explicitly acknowledged by TechInsights:

- China aggressively accumulated semiconductor equipment in anticipation of tightening U.S. export controls.

- This was not consumption but inventory insurance. The “overcapacity” that resulted is therefore not evidence of misjudgment but of successful pre-positioning – Chinese fabs now possess sufficient legacy DUV (Deep Ultraviolet) lithography and conventional deposition/etch equipment from ASML, Applied Materials, Lam Research, and Tokyo Electron to sustain production indefinitely, while U.S. sanctions prevent replacement.

The Hidden Layer: Understanding Chinese Plans in Acceleration of Domestic Capacity Ramp Up and Volume Expansion

Behind the visible equipment purchasing decline:

- Chinese fabs are executing unprecedented capacity ramp-up phases.

- Our critical insight is showcasing that: Fabrication and Construction completed physical contribution of trials for low-volume production already 12/2024. Industry sources document that “many newly built chip factories are still coming online in 2025, with even more advanced facilities expected to begin production in 2027 latest”.

This creates a specific trajectory: machines purchased in 2024-2025 are now entering full-scale production in 2026 with at least 37 facilities generating volume increases that require NO new equipment purchases. Surely the company’s Lingang (Shanghai) fab—a $8.87 billion investment with 100,000 wafer-per-month capacity focused on 28nm and above—is ramping from pilot production to full capacity utilization precisely that equipment, which is spending IC’s of Beijing fab, focused on 40nm-28nm processes and entering into pre-production. These facilities add approximately 240,000 wafers-per-month of 300mm capacity by 2026, with no requirement for proportional new equipment purchases.

The volume implications are staggering. Industry analysis projects that China’s semiconductor foundry market will expand to $14+ billion annually with mature-node (28nm+) capacity comprising 33.3% of China’s foundry market in 2024, and expected to capture 31% of global 28nm output by 2027. This is growth within existing capacity, not driven by new equipment.

The Technological Layer: Yield Improvement and Process Engineering Acceleration

The most significant hidden dynamic concerns not equipment volume but quality-per-wafer metrics. The prevailing Western assumption is that China’s chip production operates at permanently inferior yields and costs: SMIC’s 7nm process achieves ~30% yield versus TSMC’s 90%, with production costs 40-50% higher. This analysis treats yield as static rather than as a rapidly improving variable under intensive Chinese focus.

Evidence suggests yields are accelerating faster than publicly acknowledged. The Huawei Mate 60 Pro’s Kirin 9000 processor, produced by SMIC at 7nm using pure DUV lithography in September 2023, required approximately 34 lithography steps instead of the 9 steps necessary with EUV technology. This process delivered functional volume production despite theoretical yields suggesting commercial infeasibility. By 2025, nearly two years of iterative production refinement have likely improved yields substantially—industry estimates suggest 20%+ yields on SMIC’s pilot 5nm line as of Q2 2025.

This improvement trajectory follows non-linear dynamics. Each production cycle generates data that informs the next iteration. Chinese fabs are deploying advanced AI-assisted process control systems that analyze multi-sensor data to adjust parameters in real-time, potentially yielding 10-50% improvements in defect density and throughput depending on implementation maturity. A 2025 SEMICON presentation documented that AI-driven closed-loop production systems can improve Overall Factory Efficiency (OFE) by percentages that translate to substantial yield gains. The magnitude of these improvements is industry-dependent: high-volume production of mature-node chips (28nm+) benefits most, which happens to be China’s overwhelming focus.

Furthermore, Chinese equipment makers—Naura, AMEC, and SiCarrier—are making extraordinary progress in process equipment reliability and tool-specific optimization. AMEC’s etch tool deliveries grew from 1 unit in 2023 to 128 units in 2024, with expectations for “further substantial growth in 2025”. Naura’s revenue grew fivefold to ¥29.8 billion in 2024. These are not marginal suppliers; Naura now ranks seventh globally among all semiconductor equipment manufacturers. Chinese-made equipment, while inferior to ASML/Applied Materials systems at advanced nodes, offers specific advantages for legacy node production: lower capital cost, faster deployment, and—critically—integrated feedback loops that enable customization for specific Chinese fabs’ production mixes.

The Equipment Substitution Layer: Domestic Suppliers Displacing Foreign Alternatives

A crucial mechanism sustaining capacity expansion without proportional foreign equipment spending is the substitution of domestic equipment suppliers for Western vendors. By 2024, Chinese equipment makers supplied only 17% of testing and assembly tools domestically in 2023, but this ratio expanded dramatically through 2024-2025.

Industry projections suggest Chinese equipment will comprise 50-60% of total equipment used in Chinese fabs by 2030, particularly in mature nodes >28nm. This transition is already visible: Naura, AMEC, and ACM Research are gaining share in cleaning, etch, and deposition tools, areas where foreign competition is increasingly restricted or uncompetitive for legacy nodes. The strategic implication is immediate: a Chinese fab requiring 50,000 wafers-per-month capacity in 28nm processes in 2025 can deploy a mixed portfolio of refurbished foreign and new Chinese equipment, dramatically reducing capital expenditure compared to deploying exclusively new ASML/Applied Materials systems.

The refurbishment market itself is explosive. China’s semiconductor equipment refurbishment market, valued at $10.72 billion in 2025, is projected to grow at 11.89% CAGR to $21.03 billion by 2033. This creates a secondary economy in which DUV lithography machines, deposition and etch systems from the 2023-2024 stockpile are refurbished, upgraded, and redeployed within Chinese fabs with minimal new equipment purchases. Refurbished 300mm equipment and consumable parts cost tens of millions less per tool than new systems, with estimated savings of $10-50+ million per tool on average.

The Throughput Expansion: Volume Metrics Behind Equipment Spending

The counter-intuitive dynamic: China’s semiconductor chip exports grew to $128+ billion in 2024 (tracking toward $138+ billion annually), with domestic production estimated at $280+ billion to support domestic consumption. If production is expanding while equipment spending contracts, the only logical explanation is utilization of existing capacity at higher throughput rates.

Capacity utilization in mature nodes improved from crisis levels (60-70% in H1 2024) to 75%+ by H2 2024 and is projected to stabilize above 80% in 2025. This translates directly to volume expansion without equipment multiplication. A fab at 60% utilization produces far fewer wafers than the same fab at 80%+ utilization, and crucially, requires no new equipment to achieve the improvement—only operational optimization and demand stabilization.

SMIC’s explicit warning about “oversupply risks in mature-node chips” in February 2025 signals that production capacity has expanded sufficiently to create competitive pricing pressure—exactly the outcome one would expect if volume per unit is increasing while equipment purchases decline.

The Hidden Frontier: Advanced Node Production Acceleration and Process Technology Breakthroughs

The most significant “behind the scenes” development concerns progress in sub-7nm production, occurring despite or perhaps because of equipment spending constraints.

SMIC successfully produced 5nm chips in 2024-2025 using Self-Aligned Quadruple Patterning (SAQP) techniques—essentially stacking four DUV lithography passes to achieve 5nm-class resolution. This represents a fundamental technique shift, not merely optimization of existing processes. By Q2 2025, industry sources suggest SMIC’s 5nm pilot line achieved 20%+ yields with roadmaps extending toward 3nm using increasingly complex patterning schemes. While 20% yields are commercially marginal compared to TSMC’s ~70-90%, they represent functional production—chips are being manufactured and deployed in Huawei devices.

The strategic significance is geopolitical, not immediately economic. SMIC’s demonstrated ability to produce 5nm chips—a technology node Western analysts deemed impossible without EUV lithography—validates China’s technological trajectory. Each increment toward commercial 5nm production, and especially toward a viable 3nm roadmap (however yields-limited), strengthens China’s negotiating position and reduces Western leverage.

Furthermore, evidence suggests Chinese lithography tool development is accelerating. Huawei is testing domestic EUV lithography elements at its Dongguan facility, with trial production of circuits scheduled for Q2 2025 and full-scale manufacturing projected for 2026. The system reportedly uses Laser Discharge Induced Plasma (LDP)—a lower-cost alternative to ASML’s Laser Produced Plasma (LPP) approach. While credibility remains uncertain, the sheer scale of investment and the intensity of effort suggest trials will occur as scheduled.

Additionally, China’s e-beam lithography alternative (Xizhi machine developed at Zhejiang Lab) introduces a fundamentally different patterning technology, orthogonal to ASML’s photon-based approach. E-beam systems are slower and lower-throughput than photon lithography but offer precision advantages and—crucially—don’t depend on light source technology that ASML monopolizes.

The Strategic Lever: Domestic Capacity Expansion Generates Substitution Within China

China’s semiconductor import-replacement strategy operates as a closed loop. As domestic foundries increase output at 28nm and above, they displace foreign suppliers within the Chinese market. China’s semiconductor imports declined 10% in 2023 and are projected to decline 10-15% in 2024, with forecasts suggesting 20% annual decline in future years as domestic substitution accelerates.

This creates a “crowding out” effect: every wafer manufactured by SMIC, Hua Hong, or other Chinese foundries displaces a wafer that would have been imported from TSMC, GlobalFoundries, or UMC. In mature nodes (28nm+), this is commercially viable and economically brutal for non-Chinese foundries. The Chinese government has targeted 70% domestic chip production by 2026—a goal that, while still unlikely, represents a 30+ percentage point improvement from ~40% in 2024.

From a capital allocation perspective, China’s equation is therefore: Why purchase new ASML/Applied Materials equipment to run at marginal utilization when existing equipment generates volume production at 28nm+? The answer is obvious—and explains equipment spending contraction despite capacity expansion.

The Geopolitical Implication: Self-Sufficiency Asymptotes Faster Than Western Strategy Responds

The fundamental thesis:

China is achieving semiconductor self-sufficiency not through breakthrough innovation but through patient, relentless optimization of existing technology combined with systematic import substitution and domestic equipment provider development.

By 2026-2027, China will have achieved:

- 40%+ mature-node capacity growth using mostly existing equipment (no proportional new purchases required)

- Functional sub-7nm production (5nm at modest yields) that enables Huawei’s strategic products

- 50%+ domestic semiconductor equipment penetration for legacy nodes, reducing dependence on foreign suppliers

- Refurbished equipment ecosystem supporting continued capacity utilization without new foreign imports

- AI-assisted process control delivering incremental yield improvements of 10-50% depending on implementation

- Emerging domestic lithography alternatives (EUV trials, e-beam systems) reducing long-term equipment dependency

The apparent “overcapacity” is therefore not a crisis but a transition point.

This Decline-Signal is a “Strategic Victory” for China/Russia Alliance

WE are pretty sure about the following:

- A decline in Chinese equipment purchases should be interpreted not as industrial weakness but as the successful transition to a new equilibrium.

- China stockpiled equipment at extraordinary cost (2023-2024 spending of $50+ billion annually versus typical levels of $20-30 billion) specifically to enable this transition.

- The “overcapacity” represents positioned inventory, not stranded assets.

- Hidden capacity expansion occurs through existing equipment deployment at higher utilization rates, domestic equipment substitution, and process technology optimization that generates greater output-per-wafer without proportional equipment multiplication.

PLEASE CALL ME, IF YOU LIKE FURTHER DISCUSSIONS ON THIS TOPIC